In this article we will discuss:

- Medical marijuana history

- The Marihuana Tax Act

- Rediscovering the medical value

- Marijuana nowadays

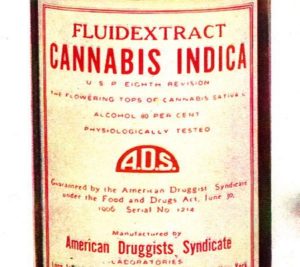

Marijuana, botanically known as cannabis, has been around for millennia. There are several species or varieties of cannabis, most notably cannabis sativa and cannabis indica. Up until 1937, the drug was basically legal in the United States and was often prescribed medicinally. Even though it’s been prohibited for 75 years, it is still one of the most commonly used drugs in America.

Medical marijuana history

Cannabis has been used both medicinally and recreationally since ancient times. In China, it appears in the Pen Ts´ao as a treatment for “gout, rheumatism, malaria, beriberi, constipation, and absentmindedness.” The Pen Ts´ao is traditionally ascribed to legendary emperor Shen-Nung who is said to have lived in the 3rd millennium BC (although some modern historians date his life to the 1st century AD). Famous surgeon Hua T’o was supposed to have used cannabis to perform painless operations as far back as the second century AD. Eastern Indian documents in the Atharveda refer to the medicinal use of cannabis all the way back in the first millennium BC.

For an in-depth article about the workings of medical cannabis, visit our friends of Spliff Seeds and read their blog about medical marijuana trials

Cannabis was also mentioned in several medicinal texts by the ancient Assyrians, who referred to the hemp plant as “qunnabu” (an apparent etymological cognate of “cannabis”). Some Biblical scholars believe that “qunnabu” is the same as “kaneh bosm” (translated as ”aromatic cane” in Exodus 30:23, a verse in which God orders Moses to make a holy oil composed of cinnamon, kaneh bosm, and kassia) (Russo).

In the Roman world, cannabis was described in the classic medical writings of Galen and Dioscorides, both of whom imaginatively recommended the “juice of the seed” to ward off earaches, sexual disinterest, and flatulence. It was also regularly prescribed as an analgesic or painkiller.

In 1994, the oldest archeological evidence of medicinal cannabis use was discovered in an Egyptian tomb dated back to the third century AD. The tomb contained a young girl who had died in childbirth alongside traces of hashish (concentrated cannabis resin) which had likely been used to ease labor pains.

An Irish physician, William B. O’Shaughnessy, brought knowledge of the medical properties of cannabis to Europe in 1839. He observed its use in India and then experimented with alcohol-based cannabis tinctures to try to treat rheumatism, rabies, cholera, tetanus, and convulsions. He described it as an analgesic and an “anti-convulsive remedy of the greatest value.” In Victorian times, cannabis came to be popular as a method of treating asthma, migraines, neuralgia, senile insomnia, and painful menstruation and childbirth. By the late nineteenth century, however, its use began to wane as stronger, more conventional medicines became available.

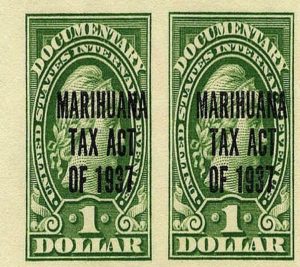

The Marihuana Tax Act

Marijuana’s legal medicinal status was ended by a political misfortune. In 1937, the Marihuana Tax Act, a bill designed to ban marijuana entirely, was brought before Congress. The director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Harry Anslinger (who was, by the way, a former Prohibition official), led the attack on marijuana with spurious charges of madness and violence that focused on Hispanics, African Americans, and other minorities.

One of the most vocal groups to oppose the bill was the American Medical Association (AMA). Dr. William Woodward, the AMA’s chief spokesperson, argued that cannabis was not dangerous and that its medicinal use would be severely curtailed by the proposed measures. The Prohibitionists prevailed through the use of a well-organized campaign of misinformation. Since then, marijuana has been functionally illegal in the United States.

Of course, the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act effectively ended the use of cannabis as a medicinal remedy. By 1941, it was completely taken off the U.S. pharmaceutical market because no one could conform to the burdensome requirements of the law.

Nevertheless, government-sponsored panels of medical experts continued to find marijuana harmless and even potentially useful. In 1944 an expert panel of the New York Academy of Medicine organized by New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia concluded that marijuana was not addictive, did not lead to abuse of other drugs, and that public hysteria about it was completely unfounded. Commissioner Anslinger vehemently denounced the report and sought to destroy as many copies as possible. In 1971, President Nixon appointed the Presidential Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse led by Pennsylvania Governor William Shafer. When the commission unexpectedly recommended the repeal of laws against adult use of marijuana, Nixon quickly trivialized and disavowed their report. Another study by the National Academy of Sciences came to similar conclusions in 1982, and was accordingly ignored by President Reagan.

Rediscovering the medical value

The medicinal value of marijuana was rediscovered during the recreational marijuana boom of the 1960’s. By the early 1970’s, it was reported that some young cancer patients found that smoking a joint could relieve the gut-wrenching nausea that resulted from chemotherapy. Clinical studies at Harvard and elsewhere soon confirmed marijuana’s beneficial anti-nausea properties.

Meanwhile, other patients were discovering that marijuana could help diminish the effects of glaucoma, chronic pain, and muscle spasticity from spinal injuries and multiple sclerosis (among other physical maladies).

In the late 1970’s over 35 states passed legislation that established medical marijuana research programs. Of course, each of those programs was eventually shut down by federal drug regulators, making it near impossible to conduct and produce scientifically legitimate research on medical marijuana.

According to the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, marijuana is considered a Schedule 1 controlled substance, meaning that, essentially, it has the potential for high abuse or addiction and has no recognized medicinal properties. Schedule 1 drugs cannot be used with express consent from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This process required exhaustive paperwork, long delays, and, usually, certain refusal.

In 1972, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) petitioned the government to make marijuana a Schedule 2 substance which would make it available for medicinal use. This action developed into a lawsuit that dragged on for 20 years and ended in defeat for NORML. In the meantime, frustrated patients were forced to seek other legal (and perhaps less effective) remedies.

In 1976, Robert Randall, a glaucoma sufferer, succeeded in persuading the federal government to supply him with marijuana under a new FDA “Compassionate Use” protocol. With the support of his physician, Randall argued that marijuana was the only drug that would prevent him from completely losing his vision and won a lawsuit against the federal government. The government grudgingly agreed to supply Randall with free marijuana from its own research farm in Mississippi. In later years, more patients managed to enroll in the Compassionate Use program—a process that required complex and time-consuming paperwork to be filled out by the patient’s physician. Pressed by a flood of over 100 new applicants who had been struck by the AIDS virus, the government shut down the program for any new applicants. Today just four surviving patients still receive marijuana legally in the U.S. for conditions including glaucoma, multiple sclerosis, and other rare genetic diseases.

In 1988, following extensive testimony, DEA administrative judge Francis Young ruled that marijuana’s medical benefits were “clear beyond question” and that it should be reclassified as a Schedule 2 drug. Judge Young’s recommendation was promptly overruled by DEA chief John Lawn, who expressed concern that it would send the ”wrong message” about marijuana’s supposed harmfulness despite the fact that morphine and cocaine had previously earned a Schedule 2 classification. After further legal maneuvering a federal appeals court upheld the DEA ban in 1993. Because of this, marijuana remains a Schedule 1 drug to this day.

Even so, medical marijuana has attracted mounting interest from health professionals. Despite the fact that the AMA switched it position on cannabis after 1937, it has undoubtedly become more beholden to corporate interests. Indeed its California branch, the CMA, has called for legal and scientific research to be undertaken in an effort to establish certain guidelines for prescription cannabis use. Other organizations have been more vocal in advocating outright legalization of medical marijuana, including:

The American Public Health Association

The American College of Physicians

The American Nurses Association

The American Psychiatric Association

The American Academy of family Physicians

The Aids life lobby

The Physicians Association for Aids care

The New England Journal of medicine

Consumer reports magazine

In 1996, California voters approved an initiative that recognized the value of medical marijuana. The California Compassionate Use Act (Proposition 215) exempted patients from prosecution for possessing or cultivating marijuana for medical use as long as they had a physician’s recommendation.

The federal government, led by Drug Czar Barry McCaffrey, denounced and attacked the initiative as divergent from federal law. The government threatened to have physicians arrested for recommending marijuana, but it was blocked by Conant v. Walters—a federal court decision which held that physicians were protected under the First Amendment in recommending marijuana. The government proceeded to attack medical marijuana by targeting growers, co-ops, and dispensaries that were providing medicine to patients, with raids that ensnared one coauthor of this book, Ed Rosenthal.

Meanwhile, in 1997, Drug Czar McCaffrey commissioned the national Institute of Medicine (IOM) to review the scientific evidence on the health benefits and risks of marijuana and other drugs derived from it (known as cannabinoids). In 1999, the IOM reported that cannabinoids had ”potential therapeutic value” especially for nausea reduction, appetite stimulation, anxiety reduction, and pain relief. The report cautioned against use of smoked marijuana on account of the respiratory hazards of smoking, but acknowledged that it remained the only beneficial alternative for certain patients with chronic conditions.

The report recommended further research and clinical trials including the development of non-smoked delivery systems. The federal government, however, ignored the report and continued to oppose medical marijuana. Despite federal opposition, support for medical marijuana grew steadily following the passage of Prop. 215. Other states passed medical marijuana laws of their own including Oregon, Washington, Alaska, Nevada, Colorado, Maine, Montana, Hawaii, Vermont, Rhode Island, and New Mexico. Canada’s highest court struck down the country’s marijuana laws and ordered the government to institute legal access for medical cannabis users.

Marijuana nowadays

To this day the U.S. government continues to assert that all marijuana use (whether medicinal or recreational) is illegal under the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA). In 2005, the US Supreme Court upheld this position in its ruling Gonzalez v. Raich. The court rejected a challenge by two California patients, Angel Raich and Diane Monson, who argued that the government’s powers to regulate interstate commerce did not extend to their personal use and cultivation of medical marijuana under Prop. 215. While the court upheld the federal ban on medical marijuana, it did not question the validity or legality of the state laws. Therefore patients are still protected from prosecution under state law (though, not federal law) in the 14 states and the District of Columbia with medical marijuana laws.

In practice, the DEA and Justice Department officials have continually insisted that they have no interest in pursuing individual patients and that their main concern is large-scale traffickers. As a result, most patients who possess and grow for their own individual use have little to fear so long as they are discreet and comply with local medical marijuana laws. The threat of federal prosecution has been further diminished by the Obama administration’s announcement that it will seek to respect state medical marijuana laws.

Since the passage of Prop. 215, public use and acceptance of medical marijuana have grown dramatically. As of this writing, some 400,000 Americans are using marijuana legally. A 2002 Time magazine poll reported that 80% of Americans support legalizing medical marijuana. It is probably only a matter of time before federal law is reformed to restore the right of U.S. citizens to use and benefit from medical marijuana.

0 Comment:

Post a Comment